In the winter of 2005, Elizabeth Hargrave, a health policy analyst, took a ski trip with a group of friends from her church. The problem was, she said, she grew up in Florida, “and I don’t actually enjoy skiing, or any winter sports.” One of the friends had brought a selection of board games—Settlers of Catan, Ticket to Ride, the greatest hits of the tabletop gaming revolution that began in the early 2000s. Hargrave, who played bridge but hadn’t really played board games since she was a kid, was “totally hooked,” she said. “The combination of the games themselves and the fact that I didn’t want to be outside was the perfect storm.”

After she returned home to the D.C. suburbs, she continued playing games. She loved the math of them, the way they became puzzles: How many trains do you need to build a line from Winnipeg to San Antonio, or how many points will you get if you complete this six-tile walled city? In her newfound fandom, Hargrave was like thousands of adults who’ve rediscovered the joy of board games, especially as a new kind of game took over the market. In “Eurostyle” games, players complete complex, evolving challenges more involved than simply traveling around a game board answering trivia questions or paying rent. And in Eurostyle games, players are never eliminated—unlike, say, in a game of Monopoly, where players who go bankrupt have to sit around and watch everyone else complete their conquest of the board. Thanks to Catan, Carcassonne, the Castles of Burgundy, and games like them, board games transformed from an industry aimed at children, dominated by Hasbro and Mattel, to an $11 billion industry in which adventurous companies and superstar designers make complicated, $60 games for grown-ups.

As Hargrave played, though, she and her friends found themselves annoyed that all the games seemed to revolve around medieval villages, or trains, or trading economies in vaguely Mediterranean locales. “At one point we placed a moratorium on games about castles,” she said. This led her to a question: Why weren’t there games about subjects she actually found compelling? Maybe she would design one, she thought. And that led to another question: What did she like enough to want to make a whole game out of it?

That one was easy. Birds.

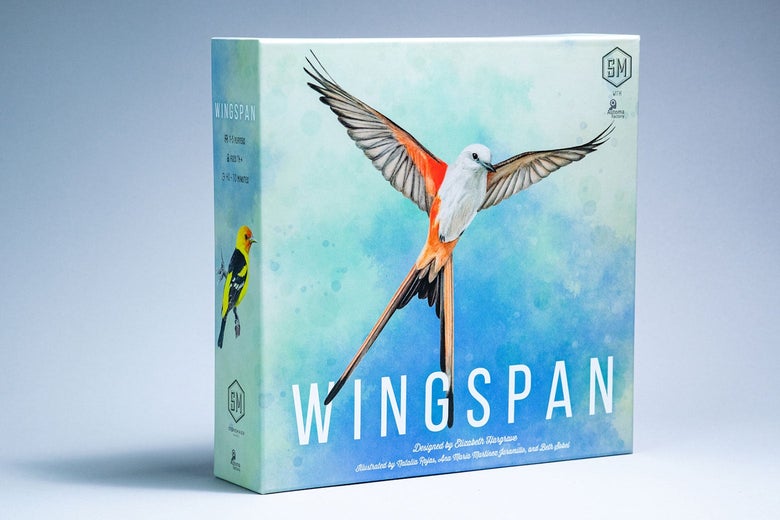

Wingspan, the game Hargrave designed and spent years testing with groups of friends, is the board game of the moment. When it was released in 2019, it was an instant hit, and that was before everyone found themselves stuck inside during the pandemic. In 2020, as the pandemic drove Americans both into their homes to stare at their families and out into the woods to stare at birds, Wingspan blew up, outselling every other game its publisher makes combined. That company, Stonemaier Games, has now sold 1.3 million copies of the game and its expansions, plus another 125,000 digital editions on Steam, Nintendo Switch, Xbox, and iOS.

My family discovered Wingspan, with its beautiful, hand-painted cards and gentle, strategic gameplay, last year, and soon we were playing it every weekend. Wingspan has transformed the way I think about games, about competition, and even about art. And I’m not alone. Wingspan has sent people flocking not only to gaming but to game design. However the board game industry transforms in the next few years, it’ll be Wingspan that causes it.

Here, open up the Wingspan box with me so we can play a game. The first thing you’ll notice is the bag filled with tiny eggs, dozens of them in cute pastels, their bottoms flattened out so they sit up straight like attentive schoolchildren. Other baggies contain round cardboard tokens that symbolize food, decorated with little green worms, red cherries, gray field mice. In our family, we collect those eggs and food tokens in little woolen nests my wife crocheted over the winter. Then there’s the dice tower: an intricately designed cardboard birdhouse that players assemble before each game. Drop the game’s dice in the opening at the back of the tower, and they come rattling out into a tray, freshly rolled. (We wore ours out, so we ordered a fancy laser-cut wood tower on Etsy.)

The stars of Wingspan, though, are the birds. Inside a bright plastic container nestle 170 cards, each bearing a beautiful hand-painted image of a bird in action. A white-throated swift slicing through air, wings extended. A yellow-billed cuckoo perched on a twig, brows furrowed quizzically over its down-curved, golden beak. A California condor, disheveled and grumpy in its black robes like a judge at the bench. Icons display what food the bird eats, where it lives, what kind of nest it builds. Each card even features a little factoid about the bird’s behavior, habitat, or conservation status.

In Wingspan, you, the player, control a small wildlife refuge, a little patch of ground with some forest, some grassland, a marsh. Your job is to populate the preserve with a flourishing array of birds. To play a bird, you need food; the Carolina chickadee, for example, requires one invertebrate token or one seed token. Each bird is worth a certain number of points, but it also has special powers that, over time, accumulate value for your sanctuary. Often, those powers are related to the bird itself and the way it behaves in the wild. The cuckoo, for example, is an occasional nest parasite, laying its eggs in other birds’ nests when food is abundant. Once you play the yellow-billed cuckoo card in your forest, each time another player’s birds lay eggs, your cuckoo lays an egg too.

Wingspan is what’s known among serious gamers as an “engine-building game,” which means that as the game goes on, the combination of birds you play becomes more and more efficient at generating points each turn, like an engine running faster and faster. Your cuckoo lays eggs, and the eggs not only give you points but make it possible to play more birds, which also give you more points but have their own powers that generate points in other ways. I prefer thinking about the mechanism of Wingspan not as an engine I am building, but as an ecosystem I am fostering. If I’ve strategized well, the birds in my ecosystem will be knitted together into a web of complex, mutually beneficial relationships. Activating the cascading effects of these healthy interconnections is the greatest pleasure of playing Wingspan.

It’s those interconnections that Hargrave began mapping out in a ginormous spreadsheet once she decided she really did want to design a board game. For four years, she researched birds, brainstormed play ideas, and—most crucially—tested the game, over and over, every week for years, with a group of friends who helped her refine her vague idea for a game about birds into an experience that’s engrossing, contemplative, collaborative, and even beautiful.

I met Elizabeth Hargrave for a walk through a park in suburban Maryland, where she lives with her husband, a horticulturalist and landscape designer. The forest, dense with cypress, poplar, and birch, seemed like a suitable locale. Wingspan is imbued with a real sense of wonder at the natural world and the place these birds occupy in it. That comes from Hargrave’s history as a nature lover and birder, the kind of person who pooh-poohs her own ability to identify bird calls but then, in the middle of a conversation, cocks her head and says, “Oh, that’s a Carolina wren. They like to repeat three, four, five times in a row.”

Hargrave is a slight, friendly woman who considers questions cautiously before answering, searching her memory for data that might back up her point. When I told her that I would find the play-testing experience daunting—week after week of people telling you what’s wrong with your game—she smiled. “The first few times I did play-testing, it was terrifying,” she said. “But you become friends with other people at the play-testing groups, and then they’re a lot less scary. Plus, you play their games, which also suck when they start. So that helps.”

There were times, Hargrave said, when she didn’t necessarily believe all the work she was putting in would prove to be worth it. “But I just latched onto the puzzle of it,” she continued. “With every play test, I could see something I could do to make it better. You see the progress that you make from other people’s feedback, and that’s very gratifying.”

“So making the game better itself became a kind of game for you,” I said.

“Yeah,” Hargrave said. “You know, I do logic puzzles for fun. I’m into figuring out, ‘Why isn’t this working? How can I make it work better? What’s going on under the hood?’ ”

From the very beginning of play-testing, what her friends and family consistently told her was the part of her game they liked the most was simply collecting and admiring a board full of birds. This tracked with Hargrave’s birding experience, in which the joy is not only seeing the bird in the wild but constructing your list. (While we walked, Hargrave opened up her account on the popular citizen-scientist app eBird. Her life list contains 755 birds.) During the years she was playtesting Wingspan, she worked as a health policy consultant, often running focus groups, and her experience with analyzing data and interpreting consumer response was also crucial to Wingspan’s development. The numbers work in Wingspan. What seems at the beginning like a set of coincidences or accidents reveal themselves by game’s end as a cleverly designed system that ensures everyone finds a way to score points.

When Hargrave felt she had a solid game, she cold-emailed every publisher that seemed like it might be amenable to a game about birds by a first-time designer. Most ignored her or turned her down, but in 2016 she did land a few meetings at Gen Con, an Indianapolis board game convention. One executive, Jamey Stegmaier of Stonemaier Games, listened to her pitch for Bring in the Birds, as it was called, responded with a list of suggested changes, and told her that if she revised the game and came back to him, he’d consider it. That meant another half-year of unpaid work before Stegmaier accepted her revision and agreed to manufacture the game. Hargrave, as a first-time designer, received no advance, so until the game sold, she wouldn’t see a dime.

But boy, did the game sell. (Hargrave declined to give a precise earnings number, but she did say she makes more in a year from Wingspan than she made as a consultant.) Stonemaier’s entire 10,000-copy first printing was snapped up before the official on-sale date, and then it continued to sell to gamers but to all new audiences as well. Birders, of course, who read about the game in Audubon magazine and responded to the game’s scientific accuracy (the vivid bird paintings, for example, by Natalia Rojas and Ana Maria Martinez Jaramillo, are wonderfully true to life). Hargrave decided early on that she wanted Wingspan’s rules to be complicated enough to appeal to a serious gamer, but not too complicated. “My goal was to find a sweet spot,” she said, where die-hard gamers would find challenges but where Wingspan would still be “accessible to people who hadn’t necessarily played a lot of board games.” That’s what happened in my family: Both parents and teens were able to figure out the basics of Wingspan in about 15 minutes but have continued to discover wrinkles and surprises that keep the game fresh.

There’s another previously underserved audience that’s responded to Wingspan: women. Stegmaier doesn’t have gender breakdowns of who’s purchased Wingspan, but he does note that the game’s official Facebook group is 40 percent women—which may not sound particularly high, but the group for Stonemaier’s other bestselling game, Scythe, is 90 percent men. Hargrave, for what it’s worth, says she has received variations on the same email over and over from male gamers: Finally, a game my wife will play with me!

Scythe, with its grim artwork and elaborate rules, is a great example of the kind of game the hobby game industry has traditionally made—the kind of game Hargrave, all those years ago, was reacting to. It’s difficult for players new to gaming to learn, its vibe is morbid, and it seems fair to say that its subject matter (battling for economic and military supremacy in 1920s Europe, with giant war machines) does not have the widest cross-gender appeal. Wingspan, by contrast, is bright and lively, its cover featuring a scissor-tailed flycatcher against the backdrop of a blue sky. Its subject matter—birds—aligns with a pastime that, despite impediments, has long been enjoyed by a large population of women.

It’s easy to make generalizations on the issue of gender and games. In my family, and in Hargrave’s, the men are more competitive than the women. Hargrave said her husband really wants to win games, and if he doesn’t win, he enjoys the experience less. “But I’m like: Winning is very slightly better, but I’m just happy to have played a game.” On this issue, too, Hargrave is interested in the research, the data. She likes to cite surveys and academic studies that suggest women are more likely to be motivated by an accessible game that encourages community and is relaxing. Men, meanwhile, are more likely to be motivated by games that are strategic and competitive, preferably with direct conflict with other players.

Crucially, it is difficult to play Wingspan in a way that brings you into direct conflict with others. Indeed, it’s possible to make plays in the game that help your opponents, and the game encourages such moves—playing a bird, for example, who not only collects food for you but for everyone. That’s why, in general, you tend to score more points when you’re playing with more people. Success, in Wingspan, is not a zero-sum game. When my family first started playing the game, I, a competitive dad, chose the variation in which only one player can maximize the end-of-round bonuses. But to my surprise I soon agreed with my kids that it was more fun to play the variation in which everyone has the opportunity to score the maximum bonus if they all succeed at the designated tasks. The game has really tamped down my competitive drive. I’ve found that during the hour or so it takes to play, I rarely have any sense whether I’m winning or losing. And at the end, I am curious to find out how I did, but my enjoyment does not necessarily correlate with my victory or defeat.

And I think that the game’s sly cooperative nature—the way Hargrave’s design gently pushes you not to beat your neighbor but to succeed with her, together—goes hand in hand with its conservationist spirit. Of course passionate birders become Wingspan players, and Hargrave has heard from many nonbirder Wingspan fans who are now investing in bird feeders and signing up for eBird accounts (us, for example). But there’s also something inspiring about engaging with the outdoors in this constructive way, at a time when most human impact upon the environment seems so dire. Nature is not a zero-sum game, and neither is the human effort to preserve it: The more people you invite to the table to work together, the more everyone achieves.

How might Wingspan’s success make the board game industry different? Amber Cook, a games commentator and brand strategist, said that for starters, the example of Wingspan “has really made publishers understand you don’t have to do the same thing you did before”—that there are untold untapped markets out there, waiting for a game of their own.

Just as important, though, might be Hargrave herself, whose story is a reminder that publishers don’t need to look, Cook said, to “the same old people designing a dozen games a year.” Of course, now, Cook said, “everyone wants Elizabeth’s name on a box”—since Wingspan, she’s published a game about butterflies and a game about Victorian flower language, and has several more in development—but publishers are more open to the idea of a new designer. “People are getting taken more seriously,” Cook said, “even if they’re not coming with a 30-year gaming résumé. That’s small now, but it’s big over time.”

And more of those new designers might be from formerly marginalized communities, in part because Hargrave is doing a lot of work mentoring and highlighting women designers, nonbinary designers, and designers of color. When I asked Hargrave why expanding the population that designs games was important to her, she described the current gaming industry as its own kind of engine, one that’s built to maximize the same kinds of designers and leave others out. “Publishers are targeting ‘typical gamers’ with their themes and mechanics and their big, heavy games about whatever fantasy creatures that I don’t care about,” she said. “And then it becomes this feedback loop where they’re making games for this very niche market of people, and then the people who become board game designers are coming out of that market, and then they’re making more games just like that.” She paused. “You miss out on the diversity of people and the diversity of games that different kinds of people would make.”

Gaming isn’t transforming overnight, of course. Hargrave’s already been in play-testing groups where she gives feedback and a newish male game designer dismisses her, and then someone else murmurs, “Uh, you know she designed Wingspan?”

The lack of real competition in Wingspan, its physical beauty, the grand themes it smuggles into the family rec room—they’re all enough to make you think about what a game actually is. What are the requirements for play? Does a game even require fierce competition, or scoring? Is Wingspan actually a game at all, or is it something slightly different? Is it art?

If it’s an art form, it’s a collaborative one. Unlike a painting or a movie, the game, on its own, is not yet complete. “You’re sort of creating a platform for them to have this experience,” Hargrave said. “And you want to send them signals about what the game wants them to do that are consistent with the experience that you want them to have.” When you play birds with great powers, you see those powers benefit you over and over, you see how you accrue points, so you keep doing it. “And by the end of the game,” Hargrave said, “if you follow those nudges that the game is giving you, you will have a beautiful tableau of birds. You may not have the most points, but you’ve built something.”

Thought of this way, Wingspan, the thing in the box, isn’t a work of art. It’s more like a set of paints, or musical instruments: Wingspan allows you and your family or friends to make art together, a creative journey that results in something beautiful and satisfying, if ephemeral. Each time you repack the box, you understand a little more about the ecology of the game, and so the next time you refine or upend your practice—and create something new.

The thing I find most remarkable about Wingspan is that it’s the only game I’ve ever played in which at times, the obvious, most efficient way to score points is readily apparent—often, laying eggs turn after turn—but I reject it in favor of a strategy that’s logically shakier but might produce a more elegant result. Especially toward the end of games, I strive to play one more bird card, the perfect bird for my wetlands, because I so want to see him there, because the 4 points I get for him will be so much more enjoyable than the 5 or 6 points I’d get for laying eggs.

Hargrave acknowledges that, as some early reviewers of the game complained, anyone playing the game to win might wind up, say, laying eggs over and over in later rounds. For the game’s first expansion pack, which includes 81 new birds native to Europe, she gave more birds powers that directly generate points—such as caching food or preying on other birds—so players who have built efficient engines are rewarded further. But still, she sounds unconcerned by the opinions of players who, she said, “are playing to win versus playing to build a thing and enjoy the process.” She prizes the aspect of the game that inspires players like me to forgo brute point optimization in favor of trying to make your board as beautiful as possible. “Just enjoy your birds!” she said.

And in a game that encourages building such intricate systems, sometimes that quest for beauty creates an accidental competitive advantage. The other evening my daughter Harper and I played out on the porch, twinkling Christmas lights illuminating our board, my songs-about-birds playlist soundtracking the experience. As the final round came near its close, I had a choice: I could lay eggs for each of my final two turns, or I could gamble that I’d draw a really cool bird and have the right food to play it.

Well, c’mon, that’s no choice at all. Among the birds I drew was the greylag goose—7 points, eats seeds already in my food tray, and handsome as hell. Only after I played it did I realize that its power—“this bird counts double toward the end-of-round goal”—would give me an extra point in the Round 4 bonus, which in this game rewarded you for how many birds live in your wetlands. When Harper tallied the final scores, checking and rechecking them, I won the game by a single point—the single point I’d gained from that end-of-round bonus.

Such is the power of Wingspan that Harper, normally a very competitive game player, didn’t even care that she’d lost. “Look at my board,” she told her mom. “I played a bird in every single space.” We all admired her handiwork for a moment, imagining a walk through her nature preserve: the sun through the trees, the splash of a stream, the sounds of the birds that Elizabeth Hargrave could identify but we could not—at least, not yet.

https://slate.com/culture/2021/08/wingspan-board-game-elizabeth-hargrave-review-profile.html

2021-08-16 00:38:00Z

CAIiENmVB2sTftoJrW6ms8uSY_sqFggEKg0IACoGCAowuLUIMNFnMMyu7QU

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Wingspan: Elizabeth Hargrave's board game is changing how we play. - Slate - Slate"

Post a Comment